Edward Gregory Hon

Era: World War II

Military Branch: Army

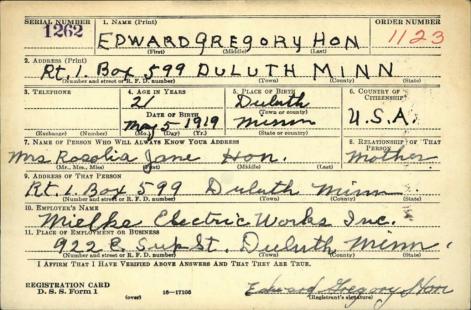

HON, Edward Gregory

Edward Gregory Hon was born on May 5th 1919 to Karl Francis & Rosalia Jane [Maunhein] Hon in Duluth, Minnesota.

Mr. Hon enlisted on March 26th 1942 at Ft. Snelling, Minnesota. He was in the U.S. Army during World War II in the European Theater. He served for 47 1/2 months ending in September 1945 and was a paratrooper of the 82nd Airborne Division.

After the war, he returned home to Duluth and married Evelyn and they started a family. Mr. Hon died on May 13th 2012 at the age of 93.

==============================

Source: “Veterans Deserve Honor, Whether They Want It or Not”, Duluth News Tribune, June 6, 2008, Chuck Frederick (see below)

Parachuting into the inky, early morning darkness 64 years ago today, Ed Hon braced himself for water. Instead, his feet caught tree branches-which then caught him.

He heard movement on the ground below, and one thought leaped immediately to mind: Germans. He knew paratroopers hung up in trees made easy targets for enemy fire.

And this was far from any ordinary jump. This was D-Day, the largest logistical undertaking ever attempted in combat and assault on Europe that would turn the tide of World War II in favor of the Allies. An estimated 150,000 men and 30,000 vehicles crossed the English Channel to Normandy that day. Hon and other members of the 82nd Airborne were among the first in. They were dropped hours before landing craft started storming beaches.

Hon was there because he wanted to be and because he knew his nation needed him to be. The second of six children raised on an accountant’s salary in Duluth’s Woodland neighborhood, the 1939 Duluth Central High School graduate had been working at Mielke Electric, tearing apart and repairing electric motors. The job earned him a deferment from military service.

“But I felt I should go. All my friends were going,” recalled Hon, now 89 and living with his wife in a rustic, year-round cabin on Island Lake, just outside Duluth. “When you’re that young you don’t think about what the consequences could be.

” Potential consequences certainly flashed through his mind as he dangled in a tree behind enemy lines. He fumbled for his firearm, found it, and then held his breath to listen.

He finally exhaled when he heard whinnying. His landing had spooked horses. He unlatched his chute and made his way to the ground, meeting with about 10 other paratroopers. Their orders were to take and occupy a bridge in St. Mere Eglise. But Hon, who had made about 10 jumps before D-Day, suspected they weren’t anywhere near St. Mere Eglise. “In that war, every paratrooper operation made at night was screwed up,” he said.

Within moments, the mission no longer mattered. Enemy gunfire shattered the stillness, scattering the warriors. Hon and two others made their way through woods across farm fields until they found a house. A Frenchman, unable to speak English, directed them to wait in a barn while he summoned a friend, a priest in training, with whom they could communicate. The friend used a map to show the Americans where they were-12 miles from their drop point.

“We weren’t even on our maps,” Hon said.

For a week, French sympathizers helped protect the soldiers. But one night, the Americans were spotted by German troops inside a “safe house” and were taken prisoner.

“They marched us toward Paris, moving us at night,” Hon said. A train in Paris waited to take them to a prisoner camp. But Hon and a buddy had other ideas.

“We escaped one night while they were marching us. I and this other guy didn’t want to continue on anymore so we jumped off the narrow country road we were on and into the bushes,” he said. “They threatened to shoot and kill anyone who tried to escape, but there so many prisoners and not many guards, so we didn’t worry about it. We had been instructed to escape, to give them trouble, and that’s what we did.

“The trees formed almost a tunnel. We laid there until everyone passed by,” he said.

They spent the night in the woods. Over the next 40 days, French farmers and other sympathizers gave them civilian clothes and helped keep them hidden while searching for ways to return them to their units.

“They protected us,” Hon said of the French Underground.” We even mixed in with the Germans at times in our civilian clothes.”

American troops, advancing from the beaches, eventually reached Hon and the others. He was identified and reunited with his unit in London.

The 82nd Airborne, he found out, suffered so many casualties it was being absorbed by the 17th Airborne. Of the 140 paratroopers he had gone to war with, Hon was one of only 12 who would return home.

As a member of the 17th, Hon participated in the Battle of the Bulge, escaping the frostbite that cost so many other soldiers’ toes and fingers. He made his last of nearly 30 jumps over the Rhine River and returned to Duluth in September 1945 after 47 ½ months of service.

Hon married his sweetheart from Morgan Park, Alta Johnson, worked as an accountant for Western Electric in Duluth and later in Columbus, Ohio, and raised five kids. After Alta died, he remarried, to Evelyn Hon.

“He has never flaunted his war experiences and never talked much about them,” Evelyn said. He only started because his children asked.

“He saw some terrible things-people getting killed and blown up or shot,” said his daughter, Cindy Hon. “I am a retired Army wife and we were stationed twice in Germany and did travel to Normandy, and those people in that area have never forgotten the Americans coming in there to free them from the German occupation.

“My dad is a very special man in so many ways,” she said. “He has an incredible story. And he’s one of the many sons of Duluth who fought in a great war and survived when so many others didn’t.

If for no other reason than that, all veterans, including Hon, deserve to be honored and thanked. Every time a flag passes by during a parade. And every time another anniversary like today’s rolls around.

“I don’t care about being remembered personally or that there’s recognition to any one soldier,” said Hon, who suffered hearing loss during World War II when a mortar exploded, killing the man standing next to him. “I guess we just trusted in God and did what we needed to do.”

Albert J. Amatuzio Research Center | Veterans Memorial Hall (vets-hall.org)